Whose stories are still missing?

On Our Bookshelf | March 2025

Dear readers,

Last week, we asked our Instagram followers: What identities are missing in South Asian literature? The responses were fascinating.

While it is more widely understood that South Asians are not a monolith, the representation gaps we heard weren’t limited to sub-ethnic or linguistic groups. We heard calls for representations of different religions and atheists, caste, neurodivergence, disability, and queerness. Others sought stories about failure, crime, living with autoimmune disorders like Type 1 diabetes, progressive minded families, realistic modern-day romances, and narratives beyond hardship. Many requested stories featuring ethnic communities like Bangladeshis or Malayalis, and diasporas in East Africa and the Caribbean.

Some responses were so niche that we struggled to find books that represented them at all: South Asian adoptees whose stories aren’t centered on birth searches, queer South Asians who aren’t disowned, cultural but nonreligious Gujaratis, third-culture kids, working-class and single-parent households.

These responses made clear that identity can be a complex weave of history, migration, culture, and lived experience. It is also inherently subjective. Society tries to use identity to define and categorize us—which is not always a harmful thing: monikers like "South Asian" can be useful to find and build a community, as we’ve done with BGB. Yet, identity is not limited to our visible or external characteristics, but often about what has shaped us. It can be "I am Bangladeshi,” or "I am a Bangladeshi Muslim woman who did not grow up repressed nor did I rebel against my family’s values." Both these identities deserve representation in literature and media.

A small but meaningful improvement did emerge when we polled our audience in 2022: an increased percent of respondents felt their identities were represented in South Asian writing. We were so glad to hear many people discovered those books through BGB. In our most recent post, we identified some books that fit the most popular responses — East African South Asians in novels like “We Are All Birds of Uganda” by Hafsa Zayyan; “Boy with a Topknot” by Sathnam Sanghera, which touches on severe mental illness, and “The Gypsy Goddess” by Meena Kandasamy, which depicts a Dalit community in Tamil Nadu.

Literature has a long way to go to capture the infinite nuances of identities in the South Asian community. We are inspired by this, too. If these stories exist, we want to hear about them. What if they don’t exist? Consider this a call to action for the writers in our community. People are craving these stories, waiting for the book that will finally make them feel seen. Perhaps that book is one you’ll write.

Until next time,

Mishika and Sri

Love, Queenie by Mayukh Sen

When I first heard Mayukh Sen talk about “Love, Queenie,” he was sitting two chairs away from me as I interviewed him at BGB’s inaugural event. We were discussing his debut, “Tastemakers,” in which he unearths the stories of seven immigrant women who shaped America’s most beloved and commercially successful cuisines—only to be willfully erased from the nation’s culinary history. Sen comically lauded that his next book drew from his obsession with soap operas. But that teaser far underplays the mastery that is “Love, Queenie.”

What excites me most is how readers will witness the curiosity and care that define Sen’s approach to writing about Merle Oberon—a woman whose life was speckled with stardust, but left unnoticed by history. During Hollywood’s Golden Age—a time marked by rigid racial barriers—and an era when the United States enforced exclusionary immigration policies against South Asians, Merle Oberon rose to the heights of cinematic fame. Yet, her success was built on a carefully guarded secret, one that, if exposed, could have ended her career: though she could pass as white, she was not. Audiences believed she was born to an affluent white family in Tasmania, yet in reality, she was the daughter of a Sri Lankan mother and a white father, spending her early, impoverished years in Calcutta and Bombay.

Her story is one of ambition and heartbreak—of love lost and found, of men, of cinema, of a fractured identity she both concealed and carried.

I can’t decide what leaves me more in awe: Merle, the subject, or Mayukh, the writer—two figures whose paths seem fated to intersect. Sen writes with a rare, reverent devotion, coating every sentence in love and admiration for his subject—much like he did with “Tastemakers.” When Sen chooses someone as his biographical subject, it’s both a compliment and a compelling reason to pick up the book—after all, he has great taste in icons.

📚 Get your copy of “Love, Queenie.”

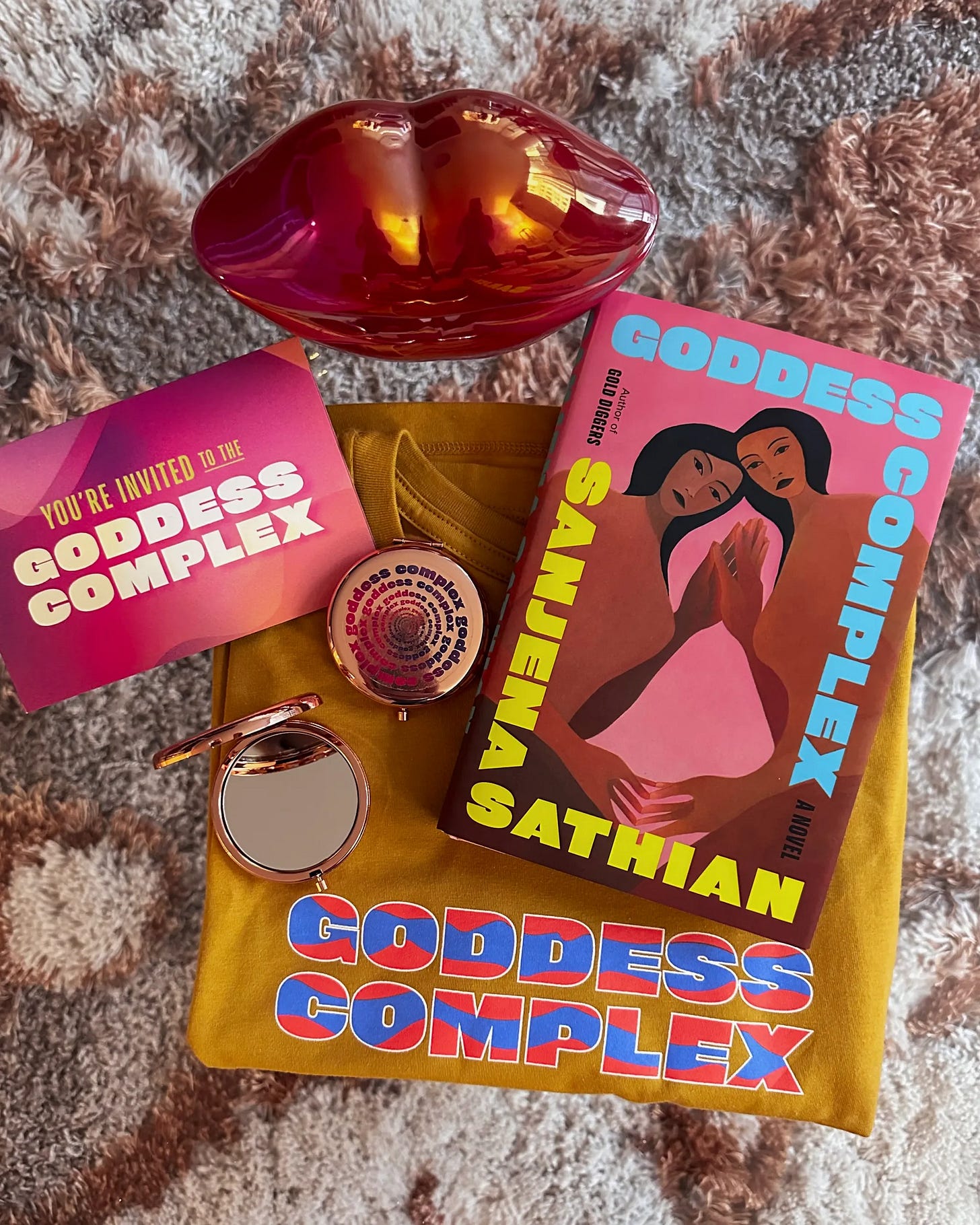

Goddess Complex by Sanjena Sathian

I saw someone coin “Goddess Complex” a comfort read, and while I admire their resilience, I have questions. It’s not cozy, but it is compelling.

Sanjana Satyananda, our protagonist, wakes up one day to find that another woman—one Sanjena Sathian—has essentially stolen her entire identity. But not just stolen it: improved it. Sathian (the author, not the unsettling doppelgänger) has crafted a novel that is equal parts psychological thriller, social satire, and existential crisis. It’s messy, it’s unsubtle, and, it’s uncomfortable.

At its core, “Goddess Complex” pokes at something deeper than just stolen identity—it digs into the contradictions of modern womanhood, especially when it comes to motherhood. The book plays tug-of-war with feminist ideals and societal expectations: Do I not want kids because I actually don’t want kids, or because I’ve internalized the idea that rejecting motherhood is the most “empowered” choice? And where do my own feelings end and the internet’s opinions begin? It’s the kind of book that makes you spiral.

The book moves with the rhythm of a fever dream—disorienting, relentless, and lingering long after it’s over.

📚 Get your copy of “Goddess Complex.”

To view all of the books featured on our page and/or purchase them from independent booksellers:

Book recommendations across identities

East African South Asians: "Migritude" by Shailja Patel; "We Are All Birds of Uganda" by Hafsa Zayyan, "Kololo Hill" by Neema Shah

Bengali or Bangladeshi: "Sunshine and Spice" by Aurora Palit; "The Magnificent Ruins" by Nayantara Roi; "The Good Muslim" by Tahmima Anam

Indo-Caribbean and West Indian: "Coolie Woman" by Gaiutra Bahadur, "Mr. Tulsi’s Store" by Brij V. Lal, "Kalyana" by Rajni Mala Khelawan

Kashmiri: "If They Come for Us" by Fatimah Asghar, "The Book of Gold Leaves" by Mirza Waheed

Malayali: “Peacocks of Instagram” - Deepa Rajagopalan , “The Covenant of Water” by Abraham Verghese, "The Illicit Happiness of Other People" by Manu Joseph

Neurodivergent (ADHD/Autism) and severe mental illness: "Boy with a Topknot" by Sathnam Sanghera; "A Great Country" by Shilpi Somaya Gowda; "Parenting at the Intersections" by Jaya Ramesh and Priya Saaral

Dalit and Adivasi: "The Gypsy Goddess" by Meena Kandasamy; The Immortal King Rao by Vauhini Vara; The Trauma of Caste by Thenmozhi Soundararajan

Sri Lankan: "The Boat People" - Sharon Bala; “Funny Boy” by Shyam Selvadurai, “Brotherless Night” - V.V. Ganeshananthan

Books set around the world

🌎 While we’re partial to featuring South Asian authored books here, our personal reading interests recognize no borders. We’re currently working through the complete Women’s Prize for Fiction longlist nominations, and love traveling the world through these stories. Where will your next read take you?

“All Fours” – Miranda July (California, U.S.A)

“The Dream Hotel” – Laila Lalami (California, U.S.A)

“Tell Me Everything” – Elizabeth Strout (Maine, U.S.A)

“Somewhere Else” – Jenni Daiches (Scotland)

“The Ministry of Time” – Kaliane Bradley (England)

“Nesting” – Roisín O’Donnell (Ireland)

“A Little Trickerie” – Rosanna Pike (England)

“The Artist” – Lucy Steeds (France)

“Good Girl” – Aria Aber (Germany)

“The Safekeep” – Yael van der Wouden (Netherlands)

“Dream Count” – Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (Nigeria)

“Crooked Seeds” – Karen Jennings (South Africa)

“The Persians” – Sanam Mahloudji (Iran, New York, California)

“Fundamentally” – Nussaibah Younis (Iraq)

“Amma” – Saraid de Silva (New Zealand, Sri Lanka, Singapore, Australia, England)

Thanks for this post! I'm writing a memoir about being a Hyderabadi Muslim - while there are some similarities with "A Place for Us" by Fatima Farheen Mirza, body image and mother/womanhood are additional themes I explore.

Lesbians. I write about lesbian literature & feminism, and have really struggled with finding lesbian South Asian stories. I'm meeting with a professor next week (who teaches a class on LGBTQI+ topics in Asia) - working to rectify this shortcoming.